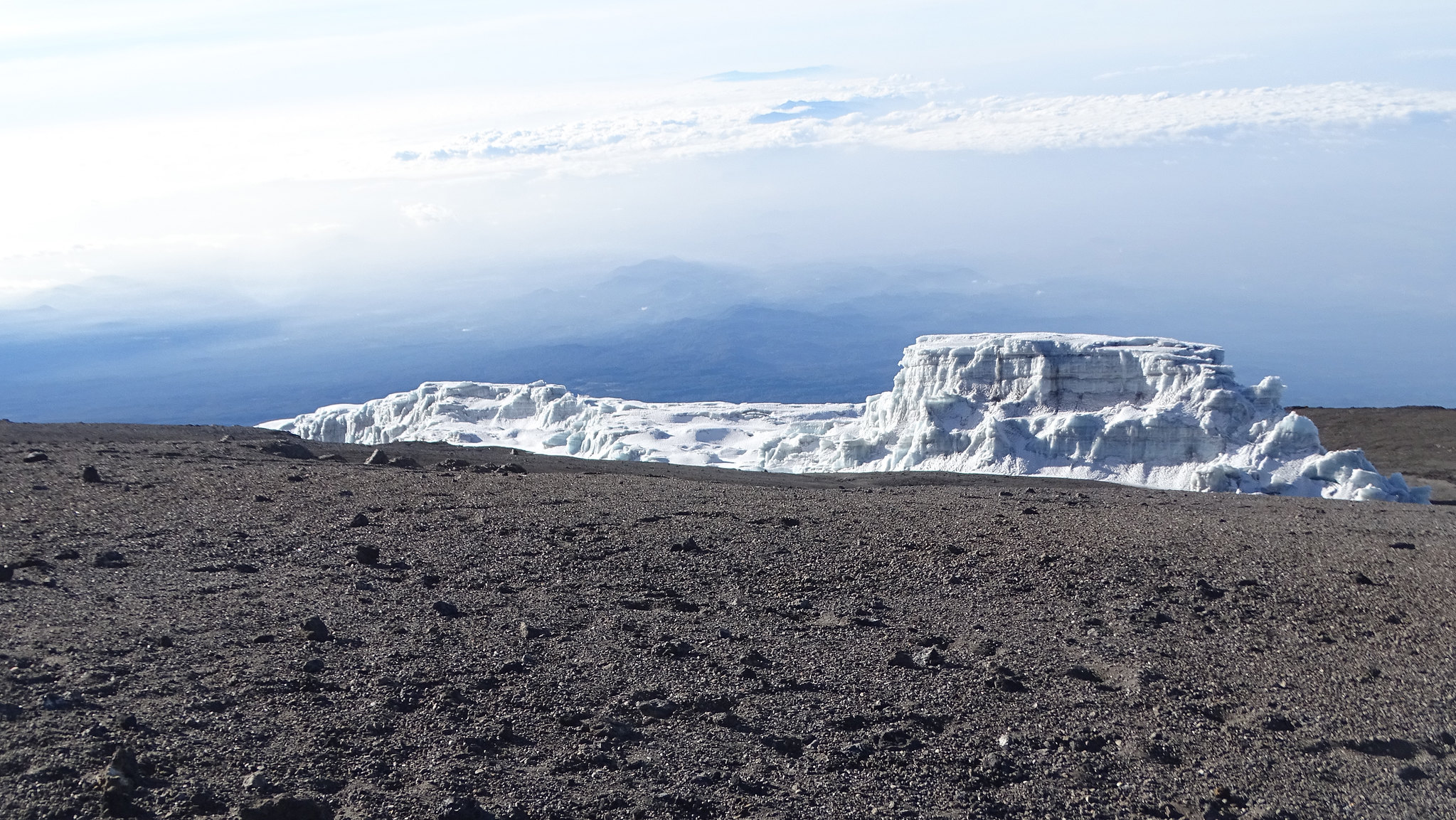

Rebmann Glacier Elevation / Altitude: 5,700 meters

The Rebmann Glacier is one of the few active glaciers that exist on the peak of Mount Kilimanjaro. After the Kilimanjaro icefields disintegrated, many icefields came out of it and few exist, the others melted away and disappeared. This glacier has diminished by a large chunk over the past 100 years between 1912 and 2000, with the mountain losing about 82% of its glacial ice. It was Rebmann, full name Johannes Rebmann who discovered Mount Kilimanjaro and in turn, this glacier was named after him.

When you begin your final push to the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro, you will traverse between Rebmann and Ratzel glaciers to Stella Point (5,685 m) a scree-filled terrain that is reported to be one of the most challenging parts of climbing the mountain.

About the Rebmann Glacier

– Located near the Southern Icefield

– Named after Johannes Rebmann, a German missionary explorer and also the first European to make a record of glaciers on Kilimanjaro in 1848.

Location of the Rebmann Glacier

The Rebmann Glacier is located to the southeast of Kibo Peak, the primary summit region of Mount Kilimanjaro where Uhuru Peak is located.

Johann Rebmann, a German missionary, and explorer had the honor of having this glacier named after him. Rebmann was the first European to see Mount Kilimanjaro and report seeing snow and glaciers in 1848.

The Rebmann Glacier, which lies close to Mount Kilimanjaro’s top, is a tiny fragment of the massive icecap that originally covered the mountain’s summit.

There are just a few places where glaciers now descend from Kibo’s crater rim. They include the Rebmann Glacier to a lesser extent, the Kersten and Decken Glaciers on the south side, all sloped at 30 to 40 degrees, and all vestiges of the ancient Southern Ice Field.

It has always been thought to be a little odd that there are glaciers in equatorial Africa. Kilimanjaro’s snows are said to have defied the ferocity of the equatorial sun, according to Johann Rebmann, who is credited with being the first European to properly recognize their presence on the summit in 1848. The recent and well-documented retreat of Kibo’s glaciers, the highest of Kilimanjaro’s three summits (5,895 m), provides solid evidence that the current climatological circumstances are unfavorable for glacier formation. Kibo still holds ice remains.

Johannes Rebmann

More than a century ago, Johannes Rebmann in 1849, to be exact, the first person to bring Kilimanjaro’s existence to the attention of the European community, noted that the Machame tribe still held on to “some tradition of a Portuguese establishment in Chagga-populated land as having taken place about two centuries ago (i.e. around the year 1650). A hill between the Pare Mountains and the Ruvu River is depicted on a map from the same Journal from 1849 with the legend, “Hereabouts is a mountain on which the remnants of a fortress and a shattered piece of cannon are supposed to be seen.”

In order to construct the first of many mission stations, Rebmann headed out towards the mountain of Kasigau on October 16th, 1847, aided by eight tribesmen and Bwana Kheri, a caravan leader.

They arrived back in Mombasa on the 27th of the same month after a successful voyage. They had heard tales along the road about the enormous mountain “Kilimansharo,” whose head was above the skies and “crowned with silver,” and at whose foot the dread Jagga people dwelt (now Chagga). Krapf promptly requested approval from the Mombasa governor before embarking on an expedition to Jagga. Although the two missionaries were increasingly interested in the fabled mountain, his stated purpose was to locate good locations for mission outposts.

The first Europeans to see Kilimanjaro disregarded warnings about the “spirits of the mountain” and left Jagga on April 27, 1848. Within two weeks, Rebmann and Bwana Kheri were standing on the vast East African steppe within sight of the peak. He writes in his journal that he could just make out “a stunning white on the mountains of Jagga.” When he asked his guide to describe what he was seeing, “he did not know but assumed it to be coldness,” the guide said. Rebmann realized right then and there that the legend was in fact genuine. On the equator of Africa, snowfields actually existed.

Rebmann’s findings were published in the Church Missionary Intelligencer in April 1849, and although they weren’t fully supported for another twelve years, they still stand as the earliest verified account of Mount Kilimanjaro.

Ratzel Glacier 5,607 m

Ratzel Glacier is a remnant of the Southern Icefield and a glacier located to the southern side of Mount Kilimanjaro’s Kibo Peak and north of Gilman’s point. It is possible to see the Ratzel Glacier’s remnant on the southern crater rim, isolated off from the vast Southern Ice Field. The Rebmann, Decken, Kersten, and Heim Glaciers, which are the four ice streams originating from the Southern Ice Field, may be divided into distinct lobes. The so-called “Wedge,” a long rock rib, currently divides the Rebmann and Decken.

In his book Across East African Glaciers, Meyer does a good job of describing the additional challenges brought on by the snow. Meyer and Purtscheller spent most of the morning chiseling a ladder out of a vertical ice cliff before getting up at 2.30 am for their first attempt on the peak. Each stair was painstakingly hewn with an average of twenty ice axe strikes. (The cliff, incidentally, was a component of the Ratzel Glacier, which Meyer named in honor of a geography professor in Leipzig, where he was born.)

The glaciers on the southern slopes were best classified as a Southern Ice Field since they had mostly lost their distinctive snouts. The Ratzel Glacier, which lay to the east, had been broken up into multiple pieces and was vanishing quickly.

Hans Meyer had not yet found the slot in the crater rim’s ice wall, which, because of the melting ice, makes the climb easier every year. Because ice axes were required to climb the Ratzel glacier, his ascent was accomplished over it.

The labour required to make each step, which required about 20 axe strokes, at such a high altitude and a 35-degree angle must have been enormous. Meyer and his companion were also in grave danger because Meyer did not have climbing gear, and any step would have unavoidably plunged them into the 3,000-foot chasm that yawns below the Western side of the glacier.

Additional information

| Routes | All Routes |

|---|---|

| Vegetation | Arctic Zone |