Scott Fischer, popularly known as Mr Rescue was one of the world’s most bravest, kind-hearted and talented mountaineers who perished on Everest in 1996 while attempting to rescue hikers. Despite having a solid track record and having climbed the world’s two tallest summits, Everest and K2, catastrophe may strike at any time, and the mountain always has the final say.

Fischer, a young man with a mix of German, Dutch, and Hungarian heritage, grew up in Michigan and New Jersey. In his early years, a TV documentary about the National Outdoor Leadership School sparked his interest, leading him to spend his summers in the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming. Despite attending Ridge High School, where he graduated in 1973, Fischer dedicated his summers to the mountains and eventually became a senior NOLS instructor.

In 1977, Fischer participated in an ice climbing seminar by Jeff Lowe in Utah. A group of climbers tackled the frozen Bridal Veil Falls in Provo Canyon. During the climb, Fischer started to climb alone on the near-vertical ice formation when his ice axe broke, leaving him stuck. His companions were able to get him a new axe, but when he climbed again, the tool slipped out, causing him to fall hundreds of feet. Fischer survived the fall but injured his foot with his ice axe. In 1984, Fischer and Wes Krause became the second team ever to scale Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa using the much dreaded Western Breach Route. In the same year, Fischer, Wes Krause, and Michael Allison founded Mountain Madness, an adventure travel service. Fischer led clients in climbing significant mountain peaks worldwide. In 1992 during a climb on K2 as part of a Russian-American expedition, Fischer fell into a crevasse and tore the rotator cuff of his right shoulder. Against medical advice, he tried to recover for two weeks and had his climbing partner Ed Viesturs tape and tether his shoulder to his waist to prevent further dislocation. He resumed the climb using only his left arm. On their first summit attempt, the climbers abandoned their climb to rescue three others, and on their second attempt, Fischer, Viesturs, and Charley Mace reached the summit without supplemental oxygen. Through Mountain Madness, Fischer led the 1993 Climb for the Cure on Denali in Alaska, organized by eight students at Princeton University, raising $280,000 for the American Foundation for AIDS Research. In 1994, Fischer and Rob Hess climbed Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen and were part of the expedition that removed 5000 pounds of trash and 150 discarded oxygen bottles from Everest. Fischer’s climb to the top of the highest peaks on six of the seven continents earned him the David Brower Conservation Award from the American Alpine Club. Additionally, in January 1996, Fischer and Mountain Madness guided a fundraising ascent of Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa.

Sandy Pittman notes that her guide Scott Fischer had been making slow progress towards the summit on the morning of May 10th. Although she noticed that he wasn’t performing at his best, she remained focused on her own climb and was confident in Fischer’s abilities. However, as a storm hit the mountain later that day, Fischer sat down and never got up. Pittman later expressed regret that she hadn’t done more to help him. Fischer had emphasized the importance of teamwork among his clients, resulting in his clients being able to help each other during the crisis. However, Pittman felt that she had not done enough to help Fischer, despite his leadership saving her life.

Scott Fischer’s body has been on Everest for almost 25 years – here is Scott Fischer’s tale and the 1996 Everest accident.

The Everest Disaster of 1996

With Scott Fischer in charge, Mountain Madness planned an Everest summit attempt for the 1996 climbing season. Fischer was under pressure to lead a successful push to the peak as well as to outperform another led crew. Rob Hall of New Zealand’s Adventure Consultants was also attempting to reach the top.

Many mountaineers have, in hindsight, linked this “rivalry” to the dangerous choices made by both lead guides.

Fischer spent the day before the summit attempt assisting a sick climber to leave Camp 1. Fisher took his time climbing to Camps 2 and 3. On May 10, about two hours beyond the strict cutoff time for a safe descent (2 p.m.), the crew finally reached the top of Everest at 3:45 p.m. The peak was reached by Rob Hall’s team well after the cutoff time. Fischer was now abnormally worn out, maybe as a result of his rescue in the days before to the summit bid. By the time the crews arrived at the peak, he could also have had severe altitude sickness.

Death of Scott Fischer

A strong storm struck the mountain immediately after both teams started their descent, leaving the climbers stuck on the South Col without appropriate shelter as if on cue from the devil himself. While the rest of his squad made it to Camp IV, safety, Fischer stayed at the South Col. He was having trouble climbing and requested Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa to descend alone while he sent back Anatoli Boukreev for assistance. The head of the Taiwanese team was among the climbers who Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa and Boukreev were able to rescue after discovering him stuck with Fischer.

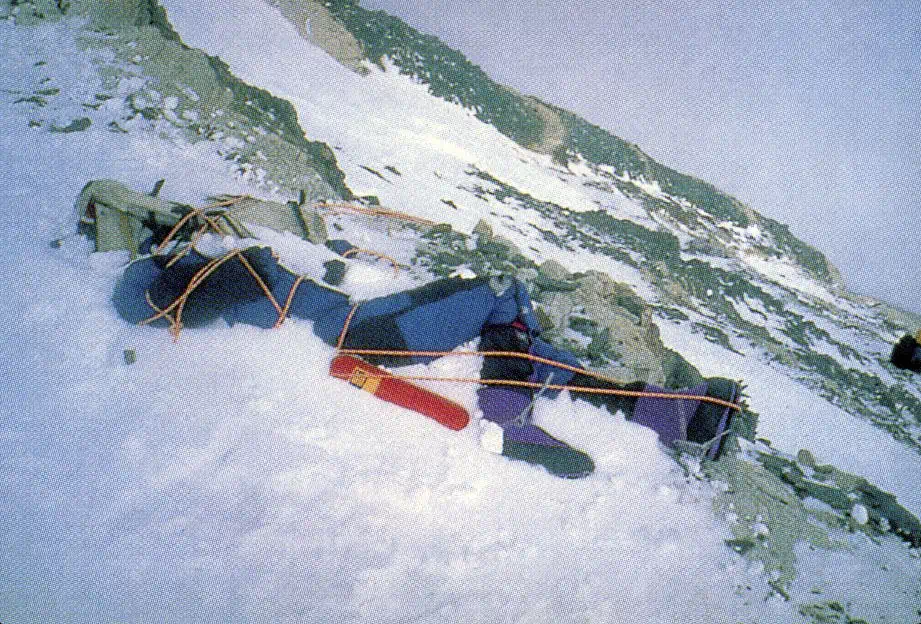

Fischer was lost, even if he was still just breathing moderately. The group decided to save the leader of Taiwan, Gao.

By the time Anatoli Boukreev came back to help rescue Fischer, his body had already gone cold, he was already dead right there at the South Col, he was 40 years old at the time of his death on Everest. In reality, Boukreev discovered Fisher half-dressed. This activity, known as ‘paradoxical undressing,’ is typically observed in the last stages of hypothermia. Boukreev encircled Fischer’s body and pushed it away from the main climbing route. Scott Fischer’s corpse is still on the mountain today. The 1996 Mount Everest accident was one of the deadliest in the mountain’s history, killing eight people.

Despite this, no other members of Fisher’s squad died. In addition to Lopsang Jangbu Sherpa and Boukreev’s bravery, Fischer’s self-sacrifice saved the lives of his clients and others on the mountain that day.

Where did Scott Fischer die?

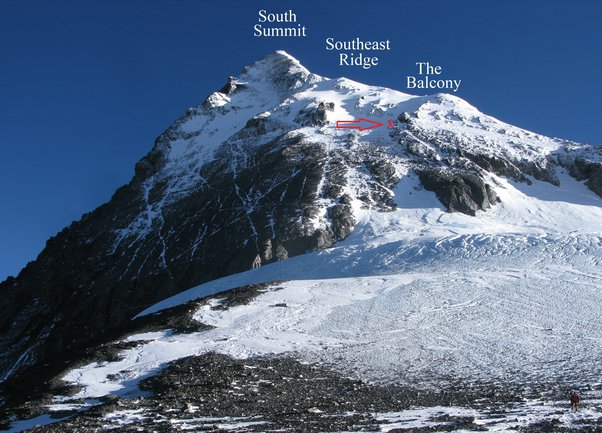

The red x on the Triangular Face marks the place near South Col along the route, from Camp 4 to the Summit, where Scott Fischer was found dead on the balcony.

As you can see, when you zoom in,

- There is a climber, at the bottom right of the photo, returning to Camp 4.

- The trail from boot marks in the snow, the centre of the photo, which goes up into the rocks towards the red x

- The trail between the red x and The Balcony is very obvious.

- There is a lone climber (a black spec) on the trail just below The Balcony.

The Rescue Mission

Fischer literally perished while trying to save his crew in the 1996 Everest disaster. That was not, however, his first unselfish gesture in the mountains. Fischer was renowned as Mr. Rescue even before the 1996 trip for his aid in countless high-altitude rescues.

On K2, he and his colleagues abandoned their summit attempt in order to assist with the rescue of Aleskei Nikiforov, Thor Keiser, and Chantal Mauduit. Despite the difficult rescue attempt, the team summited without supplemental oxygen only days later. On the same expedition, the team assisted Rob Hall and Gary Ball in descending to safety when they became altitude sick. Rescues like this are tough and unusual, which may appear callous to those unfamiliar with the ardor of high-altitude climbing.

Climbers in need of rescue are frequently left for dead. Saving them is extremely tough and dangerous in such a severe environment. Scott Fischer was one of the few people who could help. Those who knew him well believe it was his compassion for humanity that drove him to help his fellow climbers.

Over the years, Fischer and his guiding company Mountain Madness have participated in several charity climbs. Despite his celebrity as a mountain climber, Fischer was not very skilled at maintaining a thriving guiding business. His major purpose was to offer clients with unforgettable experiences rather than to gain money from them.

Who was Scott Fischer?

Scott Fischer, who was born on December 24, 1955, was a well-known mountaineer, guide, and businessman in the United States. He acquired fame by ascending the highest peaks on Earth without the aid of oxygen in addition to starting the renowned guide company Mountain Madness. Together with Charley Mace and Ed Viesturs, Scott Fischer successfully ascended K2 without using any oxygen. He and Wally Berg created history by being the first Americans to stand atop Lhotse, the fourth-tallest peak in the world. Fisher conquered Mount Everest for the first time in 1994 but tragically passed away in the 1996 Everest Disaster while escorting tourists.

Scott grew up in both New Jersey and Michigan. After seeing a program on the National Outdoor Leadership School with his father in 1970, he developed a liking for mountains.

Inspired by the movie, he travelled to Wyoming’s Wind River Range that summer and formed an unbreakable link with the mountains. Fischer dedicated the remainder of his life to peak-climbing.

In 1981, on Valentine’s day, Fischer wed Jeannie Price, whom he first met on a NOLS Mountaineering Course in 1974. The couple relocated to Seattle the following year, and there, they welcomed two children, Andy and Katie Rose Fischer-Price.

Mountain Madness

In 1984, after moving to the Pacific Northwest with his wife, Scott Fischer co-founded Mountain Madness with Wes Krause. They founded the business close to the Olympic and Cascade mountain ranges, which offered plenty of guiding chances for the Seattle-based crew. Scott was an excellent choice to head the business as it quickly expanded to include foreign activities due to his experience as a seasoned climbing instructor and natural leadership abilities. He thought that mountaineering’s challenges and discoveries may improve people’s lives.

In 1984, after moving to the Pacific Northwest with his wife, Scott Fischer co-founded Mountain Madness with Wes Krause. They founded the business close to the Olympic and Cascade mountain ranges, which offered plenty of guiding chances for the Seattle-based crew. Scott was an excellent choice to head the business as it quickly expanded to include foreign activities due to his experience as a seasoned climbing instructor and natural leadership abilities. He thought that mountaineering’s challenges and discoveries may improve people’s lives.

This was evident in his leadership and mentoring manner, and he motivated others with his fortitude, tenacity, sense of humour, and positive outlook. Everyone he climbed mountains with, even his two children, received the same instruction from him.

Wes’s fondness for the great outdoors was ignited within the rock and ice climbing community of the Western United States during the 1970s. His enthusiasm led him to venture into high-altitude climbing in Alaska and the Himalayas, eventually becoming the Climbing Leader of the 1987 American Everest North Face Expedition. Transferring his passion to East Africa, Wes arrived in the early 80s and took up the role of Director at the NOLS school in Kenya for several years. During his time there, alongside Scott Fischer, he achieved the second triumphant ascent of the Breach Icicle on Kilimanjaro. In 1983, Wes established African Environments, pioneering routes on Kilimanjaro through a series of expeditions. By 1987, the company had officially expanded its offerings to include leading safari adventures. Over the course of three decades, Wes has continued to explore the African bush, utilizing vehicles, his own two feet, and even mountain bikes. His love for nature, the great outdoors, and the people of Tanzania has served as an inspiration for African Environments to remain at the forefront of adventure tourism in the country.

In 1993, Princeton University students organized the Climb for the Cure on Denali to raise money for AIDS research. Scott Fischer and Mountain Madness participated. Fischer and Mountain Madness led a Kilimanjaro trip in 1996 in an additional effort to collect money for charitable causes.

After Fisher passed away, Mountain Madness was run by Kieth and Christine Boskoff. Together, they made significant investments in the business, saving it from bankruptcy. In 1999, tragedy struck once more when Kieth passed away unexpectedly.

Christine and Charlie Fowler perished while climbing in China only seven years later. The third owner of the Seattle company passed away within a span of 11 years. Boskoff had acquired the business with her husband, Keith Boskoff, after the founder Scott Fischer’s death on Mount Everest in 1996. Unfortunately, Keith Boskoff took his own life in 1999. Mountain Madness guide Mark Gunlogson took over operations in 2008 and effectively ran the business after that. With the help of Mountain Madness, Scott Fischer’s legacy is still alive and well. The company’s guiding principles support Fischer’s goal of providing top-notch guiding and training while still having a good time in the mountains.

What were Scott Fischer’s and Rob Hall’s biggest mistakes?

In the weeks leading up to their expedition, the leaders of the commercial team, Rob Hall and Scott Fischer, repeatedly stressed the importance of the “two o’clock rule” to their clients. This rule dictated that climbers must reach the summit by 2 pm or else turn back, as descending in the dark posed serious risks to their safety. Despite the clear rationale behind this rule, many of the 33 climbers who set out during the early hours of May 10 still attempted to reach the summit after 2 pm. Unfortunately, Hall and Fischer themselves did not reach the top until later and tragically, a violent storm struck the mountain, resulting in the deaths of five climbers in their party, including both Hall and Fischer.

Viesturs, Hall, and Fisher were highly skilled climbers who had turned their expertise into sponsorships or businesses to fund their passion. Both Hall and Fisher established expedition companies, Adventure Consultants and Mountain Madness, respectively. In the same season that Ed Viesturs was filming the Everest IMAX documentary with David Brashears, Hall and Fisher were also attempting to reach the summit. This was a crucial opportunity for both of their companies to gain publicity and establish themselves. However, the pressure of running a business may have influenced their decision-making as experienced climbers. On the other hand, Viesturs was known for prioritizing safety over reaching the summit.

He decided to start his ascent one day earlier than Hall and Fisher to avoid the congested crowd of climbers. On May 9, 1996, Viesturs, Brashears, and their team made a decision to turn back due to unstable and unsafe weather conditions. As they descended, they encountered Hall and Fisher, who were ascending with a large group of climbers from their expeditions. The sizable number of climbers caused delays, risking a descent in darkness and extreme temperature drops. Viesturs believed that compromising safety in such a treacherous environment could lead to disaster. While this is just a theory, it seems that Hall and Fisher, exceptional climbers themselves, aimed to share their love for mountaineering through their guiding businesses. In order to promote their ventures, they sought well-known clients like John Krakauer and Sandy Pittman, who were journalists reporting on their expeditions. It was mentioned that Hall was determined to reach the summit with his friend Doug Hansen, as their previous attempt in 1995 had failed. Unfortunately, due to the long queue and Hansen’s slow pace, they exceeded the safe window for descent. Hall felt responsible for Hansen’s well-being and refused to leave him behind, even though it ultimately led to a tragic outcome. In this harsh and unforgiving environment, both business and emotional decisions were being made, resulting in a devastating outcome on a particularly unfortunate day.

List of Fatalities on Everest 1996

The list of those who died along with Rob Hall in the 1996 Everest Disaster is summarized below.

| Name | Nationality | Expedition | Location of Death | Cause of Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrew “Harold” Harris (Guide) | New Zealand | Adventure Consultants | Near South Summit, 8,749 m | Unknown; presumed as falling during descent near summit |

| Doug Hansen (Client) | United States | Adventure Consultants | Near South Summit, 8,749 m | Exposure |

| Rob Hall (Guide/Expedition Leader) | New Zealand | Adventure Consultants | Near South Summit, 8,749 m | Exposure |

| Yasuko Namba (Client) | Japan | Adventure Consultants | South Col, c. 7,900 m | Exposure |

| Scott Fischer (Guide/Expedition Leader) | United States | Mountain Madness | Southeast Ridge, 8,300 m | Exposure |

| Subedar Tsewang Smanla | India | Indo-Tibetan Border Police | Northeast Ridge, 8,600 m | Exposure |

| Lance Naik Dorje Morup | India | Indo-Tibetan Border Police | Northeast Ridge, 8,600 m | Exposure |

| Head Constable Tsewang Paljor | India | Indo-Tibetan Border Police | Northeast Ridge, 8,600 m | Exposure |

![]()

Comments