Nobody remembers Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans, because Sir Edmund Hillary’s story of May 29, 1953, becoming the first person to reach Mount Everest’s summit overshadows theirs. However, a fascinating historical occurrence took place just three days earlier. On May 26, 1953, Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans, the primary climbing team in the expedition led by Hunt, were within 100 meters (328 feet) of Everest’s summit. Due to exhaustion, they turned back and descended without reaching the peak. It’s incredible to think that they were just the length of a football field away from their goal. Exhaustion can be a powerful force.

Three days after, Hillary and Norgay achieved what Bourdillon and Evans had been unable to: they made it to the summit. This news reached London on the morning of June 2, coinciding with the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. As a result of their success, Hunt and Hillary were knighted in the Order of the British Empire (KBE) while Norgay, a subject of the King of Nepal, was awarded the George Medal.

Bourdillon and Evans were both accomplished climbers. Tragically, Bourdillon lost his life at the age of 32 in a climbing accident in Switzerland, while Evans went on to be an educator in Wales until his passing in 1995 at the age of 78. Despite their pioneering achievement in reaching a previously unattained height, neither of them received recognition for their remarkable efforts.

The meeting of The Physiological Society at the National Hospital, Queen Square, in December 1953 included morning demonstrations of equipment used in the Mount Everest ascent that year. The equipment was demonstrated by three individuals associated with the expedition in various ways. The people involved were Robert Bourdillon, J. E. Cotes, and L. G. C. E (Griff) Pugh. They were all employees of the MRC and were either members or became members of the Physiological Society. Two of the same authors, T. D. (Tom) Bourdillon and Griff Pugh, were part of the Everest expedition. Robert Bourdillon was a renowned medical researcher best known for his work on vitamin D in the 1920s and 30s. Tom Bourdillon was a notable climber and mountaineer, while Griff Pugh was appointed to the National Institute for Medical Research and was a pioneer in the field of applied physiology.

The meeting of The Physiological Society at the National Hospital, Queen Square, in December 1953 included morning demonstrations of equipment used in the Mount Everest ascent that year. The equipment was demonstrated by three individuals associated with the expedition in various ways. The people involved were Robert Bourdillon, J. E. Cotes, and L. G. C. E (Griff) Pugh. They were all employees of the MRC and were either members or became members of the Physiological Society. Two of the same authors, T. D. (Tom) Bourdillon and Griff Pugh, were part of the Everest expedition. Robert Bourdillon was a renowned medical researcher best known for his work on vitamin D in the 1920s and 30s. Tom Bourdillon was a notable climber and mountaineer, while Griff Pugh was appointed to the National Institute for Medical Research and was a pioneer in the field of applied physiology.

Who was Thomas Bourdillon?

Thomas Duncan Bourdillon, an English mountaineer, was part of the historic 1953 British Mount Everest Expedition that successfully made the first ascent of Mount Everest. He tragically passed away on July 29, 1956 in Valais, Switzerland at the young age of 32. Born in Kensington, London, Bourdillon was well-educated and pursued a career as a physicist specializing in rocket research. Bourdillon was an accomplished climber and played a key role in the development of oxygen equipment for the Everest expeditions. He, along with Charles Evans, reached the South Summit of Everest on May 26, 1953, getting within 300 feet of the main summit before being forced to turn back. Unfortunately, Bourdillon and another climber, Richard Viney, died in a climbing accident on July 29, 1956, while ascending the east buttress of the Jägihorn in the Bernese Oberland.

Who was Charles Evans?

Welsh-born Sir Robert Charles Evans (1918-1995) was a prominent British mountaineer, surgeon, and educator known for his leadership in several successful expeditions. He studied medicine at Oxford University, where he became fluent in the Welsh language. After serving as a medical doctor in the Royal Army Medical Corps, he continued his passion for climbing and exploration, eventually being a part of the first ascent of Everest in 1953. Evans led the 1955 British Kangchenjunga expedition, successfully conquering the world’s third-highest peak. Afterward, he became the Principal of the University College of North Wales and was knighted for his contributions to mountaineering in 1969.

At approximately 1pm on May 26th, 1953, Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans achieved the historic feat of reaching the south summit of Mount Everest. As they gazed upon the never-before-seen terrain ahead, they were both filled with excitement and anticipation. Bourdillon captured a photograph of Evans looking towards the still-unseen summit, which has become an iconic image in the world of mountaineering. However, their time was running out, and they had to make the difficult decision to abandon their final ascent and head back to the South Col. It was a treacherous journey down, with multiple slips and falls causing immense exhaustion before they finally reached their destination. Bourdillon was haunted by regret for turning back, especially when it was discovered that the closed-circuit oxygen equipment they had been using, which was designed by his scientist father, had failed them. Malfunctioning valves in Evans’s set had caused delays and fatigue, ultimately preventing them from reaching the summit.

When they finally reached the highest point of Everest, known as the South Summit at 8750m, it became apparent that they would not be able to continue. They had been climbing at a slower pace and did not have sufficient oxygen to safely reach the summit and return. On the other hand, Hillary and Tenzing used the more dependable open-circuit equipment and were successful. Bourdillon carried his regrets until he passed away in 1956. Evans, initially a surgeon, went on to have a successful academic career despite battling multiple sclerosis. The expedition leader, John Hunt, was criticized for the way he organized the two summit attempts. It was believed that the odds were against Bourdillon and Evans and that Hunt had stacked the odds in favor of Hillary and Tenzing by allowing them a camp halfway up the southeast ridge, thus requiring them to only ascend half the distance on their summit day.

Two members of the team strongly opposed this plan initially. Alf Gregory argued that without a high camp, the first team to reach the summit would have little chance of success. Expedition doctor Michael Ward supported Gregory’s opinion, finding Hunt’s strategy to be both unusual and risky. Ward’s accusations in 1972 and 1991 caused turmoil, but new evidence discovered during the biography of Dr Griffith Pugh sheds light on the controversy, supporting Hunt and providing vital details about the expedition’s organization. This article for the Alpine Journal will outline the key issues and evidence. The open-circuit oxygen system, first used on Everest in 1922, provided climbers with a small amount of supplementary oxygen, making them feel better and reducing the need for frequent rest stops, despite not enabling them to climb much faster.

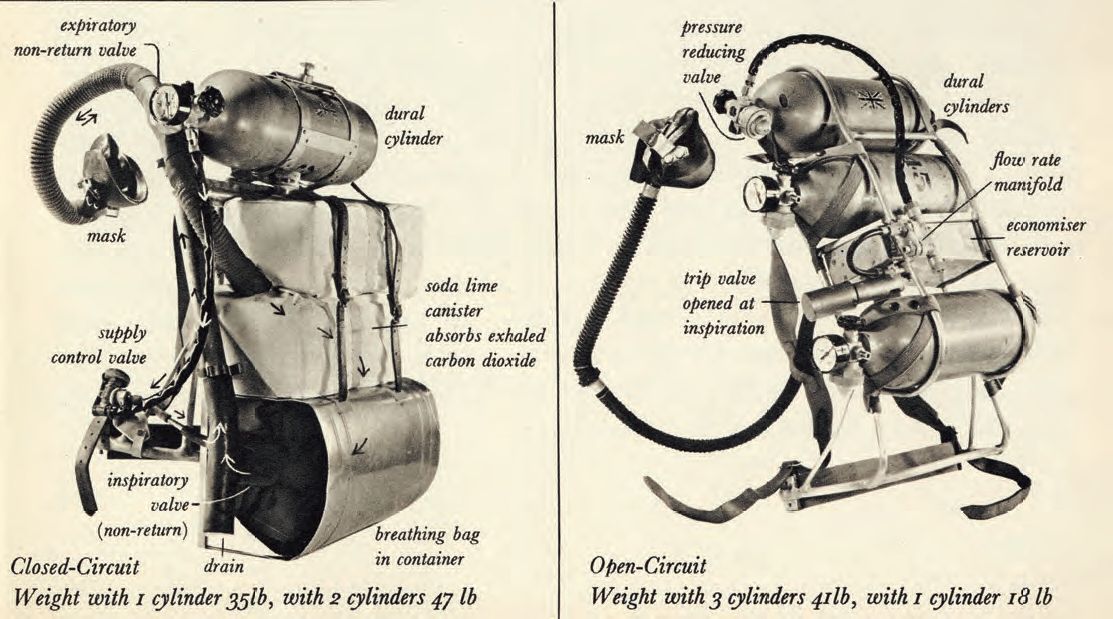

Climbers using the closed-circuit system on Mount Everest in 1936 used oxygen equipment originally designed for fire-fighting and mine rescue, allowing them to breathe 100 percent oxygen from cylinders on their backs and remain isolated from the outside air. Exhaled breath was processed through a canister of soda lime powder, which absorbed carbon dioxide and recycled the remaining oxygen back to the climber, topped up as needed by fresh oxygen from their cylinders. This system allowed climbers to breathe 100 percent oxygen for several hours, enabling them to climb much faster than with the open-circuit. However, the closed-circuit sets faced various issues such as increased breathing resistance, heat produced by the filtering process, frozen valves, and potential escape of carbon dioxide back to the climber.

The system needed a completely airtight mask, however, it had not been successfully developed yet. Tom Bourdillon and his father, R B Bourdillon, were confident they could modify and improve the sets in time for the 1953 expedition, and after substantial effort in Everest circles, they were given the opportunity to try, despite opposition from some groups. Tom was allowed to leave his government job as a rocket scientist to work on the modifications with his father. Most of the physiologists on the Medical Research Council’s High Altitude Committee were impressed with the closed-circuit, which was responsible for the 1953 expedition’s oxygen policy. Sir Bryan Matthews, the altitude expert who headed the HAC, and Griffith Pugh, who had tested the impact of oxygen at high altitude on Cho Oyu in 1952, both thought that the open-circuit system might not be sufficient, and that a closed-circuit system, like the one the Bourdillons were working on, might ultimately be necessary for a successful ascent of Everest. Concerns about the open-circuit were mainly logistical – climbers using it would not have been able to ascend fast enough or carry enough oxygen to make the full 900m climb from the camp on the South Col to the summit and return the same day.

The scientists were concerned about the difficulty of bringing enough oxygen and supplies up to the South Col for two summit attempts, and even more so for stocking a higher camp above the col. Using the closed-circuit system would allow climbers to ascend quickly enough to reach the summit and return in a single day, eliminating the need for an intermediate camp. Ten days after John Hunt became the leader of the 1953 expedition, a private meeting was arranged between Tom Bourdillon’s father and Hunt to discuss the closed-circuit system. Otto Edholm, a member of the HAC, emphasized the potential usefulness of closed-circuit sets if a proper design could be provided.

Several weeks ago, Bourdillon’s father had authored a previously unnoticed document examining the challenges of providing a high camp above the South Col. The document included estimates for the weight of loads, the number of Sherpas needed, and the additional equipment and provisions required for the Sherpas. The conclusion was that, without significant luck, the available manpower would likely not be enough for the task. However, compared to a two-day summit bid with the open-circuit, a one-day attempt with the closed-circuit would be a significant advantage. It would require less oxygen, fewer Sherpas, and fewer supplies on the South Col, which would greatly alleviate the problems. Therefore, based on the recommendation that the expedition should have at least two chances at the summit, Bourdillon’s father strongly suggested using closed-circuit oxygen for the first summit attempt without a high camp. If that attempt failed, a high camp could then be supplied for a second attempt with open-circuit oxygen. This proposal was presented to Hunt, who later confirmed his consideration of using closed-circuit oxygen for one of the expedition’s summit attempts in a letter to Bourdillon and Edholm.

He expressed his belief in the potential usefulness of the closed-circuit equipment and the importance of having it available for the final assault. If Bourdillon could produce the sets on time, he would eagerly test them on the mountain. If they were successful, it was likely that the closed-circuit apparatus would be used in the assault. Bryan Matthews and Griffith Pugh were less optimistic than the Bourdillons about resolving the technical challenges in time. They insisted on prioritizing the open-circuit system while still advocating for both systems to be taken to Everest. Pugh emphasized the desirability of having closed-circuit sets for the next Everest expedition, but reiterated the importance of not relying solely on them for oxygen application. The preparations for Everest were conducted in a secretive atmosphere.

The discussions and concerns from the background were kept away from most of the team and the public, but in a speech at the Royal Geographical Society in December 1952, Griffith Pugh revealed the doubts about the oxygen. He expressed confidence in an old-fashioned open-circuit system, but acknowledged that its effectiveness was not guaranteed. Pugh also pointed out the challenges of carrying enough oxygen cylinders to supply the climbers with sufficient oxygen up to the South Col. His remarks caused a stir behind the scenes and prompted a warning from John Hunt to be more discreet in order to avoid undermining the climbers’ confidence. When the expedition arrived in the Everest area, the redesigned closed-circuit oxygen sets were tested and appeared to perform well.

Just three days prior to Hunt’s announcement of his summit plan, Tom Bourdillon expressed his confidence in a letter from base camp that a direct attempt from the South Col to the top with the closed-circuit would be the best chance of success. As the expedition progressed, it became evident that the scientists were right to be concerned about the challenges of transporting supplies to the assault base camp on the 7900m South Col. The situation became critical when both teams of Sherpas stopped halfway up the Lhotse Face and refused to continue, citing sickness. It was only after Hillary and Tenzing, who were being saved for the summit attempt, went up to encourage the Sherpas that they agreed to continue.

A crumpled, handwritten note from Hunt, located at the main base camp, addressed to Griff Pugh at camp III, seeks assistance and indicates the intense pressure he was facing. The letter is marked with dramatic underlining and begins with “Dear Griff, Most Important. I am sending you the following two men who have failed us in our vital carry to the South Col.” He urgently requests Griff to send replacements and pleads with him not to let them down. Ferrying oxygen and supplies to the high camp above the col proved to be even more challenging. John Hunt had chosen a team of elite Sherpas for this task, but all but two backed out. While Bourdillon and Evans attempted the first summit, Hunt and Da Namgyal, the only Sherpa who agreed to accompany him, took as much as they could of the first round of supplies for the high camp but fell short of the planned altitude. After leaving their loads below the designated target, they returned to the South Col, completely exhausted – Hunt was fighting for his life and lost control of his bowels before collapsing near the col. Two days later, Hillary and Tenzing departed from the South Col. The plan was for them to be accompanied by three Sherpas and Alf Gregory carrying additional oxygen and supplies for their high camp. However, only one Sherpa, Ang Nyima, agreed to join the task. George Lowe filled in for one of the missing men, but they were still one man short. As a result, everyone had to carry heavier loads than expected. When they collected the extra supplies left by Hunt and Da Namgyal, they increased their oxygen flow to handle the added weight, using up part of the supply intended for the following day’s summit attempt.

The capacity was fully utilized. Michael Ward raised concerns about Hunt’s strategy 19 years later in his book, “In This Short Span,” questioning why Hunt had chosen an unconventional plan and denied Evans and Bourdillon the opportunity to acclimate to a high camp. He expressed his disappointment and frustration, suggesting that starting from the South Col was a doomed approach when a night at a high camp could have made a significant difference. Hunt’s leadership was also criticized by other historians and commentators, with speculations about his intentions and motives. Few have been willing to consider the possibility that Hunt had genuinely tried to give both summit parties the best chance for success.

Charles Evans’s diary, which was not published until later, reveals that there was no hidden agenda during the 1953 expedition. The diary indicates that the question of whether high camps could be provided for two summit attempts was extensively discussed by the ‘O group’ comprised of Hunt, Evans, and Hillary before the final plan was implemented. They ultimately determined that only one high camp could be managed and it would have to be given to the open-circuit pair. As a result, they reverted to the strategy suggested by Bourdillon senior the previous October. In a 1954 article in the AJ, Evans elaborated on this, expressing that the original hope was to have two oxygen attempts on the mountain from a high camp on the south-east ridge. However, after calculating the weights that needed to be carried to the highest camp, it became apparent that they could only take enough gear for one pair of climbers to attempt the summit. Therefore, they had to make a decision to either give up on the idea of two attempts or make the first one a scouting mission from the South Col.

In the same Alpine Journal, Tom Bourdillon mentioned that they would not be able to bring supplies to the top camp for more than one group attempting the summit. The closed-circuit group had to start from the Col as a result. Ward and Alf Gregory were not part of the inner-circle discussions and were unaware that the Bourdillons had been urging Hunt to adopt this plan for months. Both Ward and Gregory were used to Eric Shipton’s decision-making style, in which he liked to discuss options openly with the entire group. However, Hunt was more of a traditional military leader and admitted that he did not feel the need to explain or discuss the plan with everyone, only his confidants in the ops group. He did not believe in debating with everyone before making tough decisions.

Ward and Gregory disagreed with the lack of information provided, claiming that it would have been possible to have two high camps. Ward suggested that more Sherpas could have carried the extra loads of oxygen, but he did not realize that only two Sherpas were willing to go above the South Col and were exhausted after carrying loads for the single high camp. He knew that Bourdillon and Evans believed it was possible to reach the top without a high camp and this may have influenced the final plan. Hunt chose not to engage in the debate at the time and was hurt when Ward tried to reignite the controversy, but he never addressed the issue of providing for two summit parties to spend a night at the high camp. However, privately, in a letter, he expressed that the plan for the first assault was based on Tom Bourdillon’s wish to prove that the closed circuit equipment had the potential for climbers to reach the summit and back directly from the South Col. This was believed to be an advantage in terms of speed and endurance over the open circuit system, and it was what Bourdillon wanted to try.

As mentioned by Hunt in the same letter, the discussions were likely just an academic exercise. During the afternoon of Bourdillon and Evans’s attempt to reach the summit, the weather suddenly took a turn for the worse as they struggled back to the South Col. The following morning, the weather was so severe, with winds reaching speeds of up to 70mph, that Hillary and Tenzing had to delay their second attempt and wait anxiously on the col for another 24 hours. If Bourdillon and Evans had a high camp, they would have endured a terrible, wind-lashed night at 8000m. Given the dreadful weather conditions, it is highly doubtful that they could have made an attempt on the summit the following morning.

- Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, the first persons to climb to the summit of Mount Everest

- Assault on Everest: How rich nations assembled massive assaults on Everest to reach the top first.

- Frank Smythe – The first professional mountaineer’s secret from 1936 Everest Expedition

- Toni Kinshofer: A Mountaineering Legend Remembered

- Riccardo Cassin, legendary Italian climber who created routes up some of the world’s most difficult peaks and mountain equipment

- Noel Hanna: Legend Alpinist who has climbed Mount Everest 10 times dies during a trek in Nepal

- Rob Hall, the Legendary Founder of Adventure Consultants and the 1996 Everest Tragedy

- Ex-England and Manchester United legend Bryan Robson climbs Mount Kilimanjaro

- Jim Whittaker, the first American to summit Mt. Everest, on May 1, 1963

![]()