During the latter part of the previous century, the sport of climbing in the United Kingdom was home to a number of outstanding families whose accomplishments have been recorded in history. Among the families that contributed to the establishment of the sport in Britain and the Alps are the Walkers, the Matthews, and the Pilkingtons, as well as lesser-known families. The story of the five Hopkinson brothers from Manchester is one of the most amazing of all the families that have been discussed here. Through a combination of hard labor and talent, their father worked his way up through the ranks of the mill to become the Mayor of his hometown and an Alderman. The practice of mountain trekking was a long-standing custom on both sides of the family, and their mother was a member of the Yorkshire Dewhursts, who were linked to the Slingsbys and Tribes. During their formative years, the young Hopkinsons gained a profound familiarity with the Yorkshire dales as well as the Lakeland fells. As a result of the fact that they were frequently joined by their cousins, W. C. Slingsby and W. N. Tribe, it should come as no surprise that they quickly became interested in the emerging sport of granite climbing.

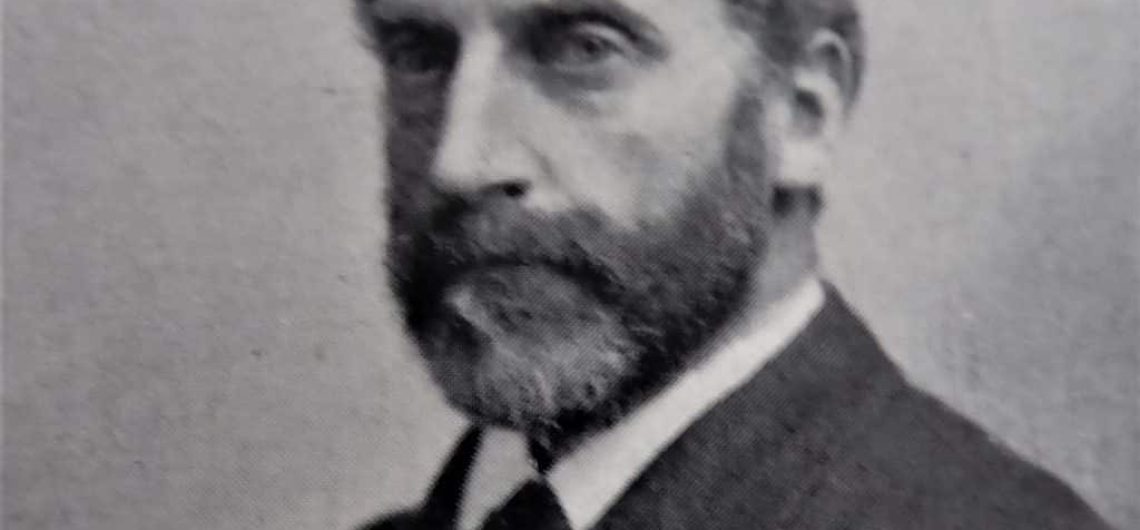

John (1849-1998) was the oldest of the five children, followed by Alfred (1851-1939), Charles (1854-1920), Edward (1859-1921), and Albert (1863-1949). John was the oldest of the five children. Maybe it was because he was the oldest child or maybe it was because he was a genius that John was always looked up to by the other members of the family; nevertheless, in reality, every single member of this unique family possessed an extraordinary amount of skill. Quite separate from their climbing, it is worthwhile to have a look at their jobs in order to gain a better understanding of the cerebral level of these individuals. John had a distinguished academic career, including serving as a Senior Wrangler at Cambridge, receiving a Doctor of Science degree from the University of London, being a Fellow of the Royal Society, and serving as President of the Institute of Electrical Engineers on two separate occasions. One of the pioneers of modern electrical engineering, he is arguably best recognized by the general public as the one who was responsible for the construction of Liverpool’s well-known tram system. Along with their brother, Charles and Edward were also engineers and frequently collaborated with him. In the year 1890, Edward was the one who initiated the introduction of subterranean electric trains in London, which marked the beginning of the present tube system.

In spite of the fact that they did not follow the engineering heritage of their family, the other two brothers were successful in their own fields of endeavor. He was a lawyer, a member of parliament, and the Vice Chancellor of Manchester University. Sir Charles Hopkinson. After being chosen Treasurer of Lincoln’s Inn, he was required to choose a crest and motto for the organization. In order to determine what the motto ought to be, he conferred with his other brothers. It is important to note that they selected the question, “Who shall separate us?” Albert was the youngest of all of them, and he entered the medical field as a vocation. His statement that “Cambridge found it could not do without a Hopkinson”—a reference to the deep relations the Hopkinson family had with the university—led him to become a prominent surgeon in Manchester and subsequently a lecturer in Anatomy at Cambridge. He went on to become a professor at Cambridge. Despite the fact that it is difficult to discover information on the early ascents of the Hopkinsons, it is known that they descended the East Face of Tryfan in the year 1882. This is four years prior to the time when Haskett Smith ascended the Napes Needle. On the other hand, their attention shifted to the Alps, where they established new routes on the Unterbachhorn and in the Fiisshorner, among other ascents. In September of 1887, Charles, Edward, and Albert Hopkinson, together with W. N. Tribe, made an attempt to down the steep face of Scafell Pinnacle. This was their first significant contribution to the sport of rock climbing in the United Kingdom.

They were halted at a place around 250 feet away from the screes, on a somewhat narrow ledge. Edward Hopkinson had just finished constructing a heap of stones at this moment. At that time, Hopkinsons’ Cairn was a magnet that attracted all of the top climbers in the world. Numerous attempts were made in an effort to get to the tantalizing mound of stones that was located farther below. The first effort was conducted by Charles himself in December of the same year, but it was unsuccessful owing to ice around 150 feet above the ground. The first significant climbing accident to occur in Britain occurred in 1903 when three climbers were killed while attempting to reach the cairn atop the mountain. The issue was not resolved until 1912, when the legendary Herford, who was climbing on the vital pitch while wearing stockings on his feet, ran out of rope when he climbed 130 feet away from the top. The Hopkinsons discovered a more straightforward path to the summit. Through the process of climbing Deep Ghyll, they were able to acquire a large fissure that they named Professor’s Chimney in reverence for John. A well-known group launched an assault on Scafell in the year 1888 using Steep Ghyll. William C. Slingsby was the leader of the group, while Edward Hopkinson, W. P. Haskett Smith, and Geoffrey Hastings were all members of the group. After turning out onto the face at the base of the big pitch of the gully, Slingsby ascended the chimney that now bears his name and which was to become one of the most popular routes in the Lake District. He did this while running out of rope that was 110 feet long.

During the same year, Hastings led Great Gully on Dow Crag, and Edward Hopkinson was there to accompany him once more. A few months later, he returned with his brothers when they climbed the gully once more, this time leading the first and most steep pitch direct. The gaunt buttresses of Dow were likely appealing to him since he returned with them. There is no question that the Hopkinsons must have accomplished a great number of new climbs that were not recorded, and it is a fair indictment of them that they failed to recognize the role that they were playing in the development of a new sport. To tell the truth, their most significant “discovery” was not documented for three years; it was the northern face of Ben Nevis. On the other hand, in 1895, they unwillingly published a tiny paragraph in The Alpine Journal in which they mentioned the fact that in 1892, they had participated in several intriguing scrambles on the peak. They had accomplished the first climb of the North East Buttress (although the name of the path that they used is unknown) as well as the first descent of Tower Ridge. They attempted to climb Tower Ridge, but the Great Tower intervened and prevented them from doing so. Norman Collie’s journey to Scotland in 1894 marked the beginning of serious rock climbing on the Scottish mainland. There is little doubt that the Hopkinsons’ enthusiastic comments to their climbing friends were the driving force behind Norman Collie’s determination to visit Scotland. In 1895, the brothers went back to Dow Crag, where they had previously completed the two climbs that have brought them the most fame to this day. Edward and John, along with a climber called Campbell, completed the first ascent of Intermediate Gully, which was an extremely difficult and exhausting climb. At the same time, Charles was leading Hopkinson’s Crack, a tour de force that is still considered to be one of the most difficult severes in the region.

The Haunted Mountain :

The Petite Dent de Veisivi, is the location where the family incurred a terrible loss.

On the other hand, in the year 1898, this remarkable family was struck by a terrible catastrophe. Arolla, which is located in Switzerland, was the location where John Hopkinson, his wife, four boys, and two daughters were staying during the summer of that year. A number of the prominent climbs, including the challenging Arolla face of the Za, were completed by them without the assistance of a guide. The father, together with his son Jack, who was 18 years old, and his two daughters, who were 23 and 19 years old, embarked on a journey to traverse the Petit Dent de Veisivi together on the 27th of August. Following the fact that they did not return that evening, a search team was organized, and the bodies of the individuals were found beneath the south face of the mountain the following Monday morning. Although it was evident that they had fallen from a position near the top, it was hard to determine whether they had fallen as a result of a slip or because of falling stones. To this day, it continues to be one of the most heartbreaking events that occurred in the Alpine region. There was nothing that the surviving four brothers could do to alleviate their anguish, despite the fact that they went out to the scene of the accident as soon as they could. His favourite, John, was no longer with them. They did not climb again after that. There is a sad little footnote to the narrative of the clever Hopkinsons, which is that both of John’s last two boys were murdered in the Great War. This brings the story to a heartbreaking conclusion.

Who was John Hopkins?

John Hopkinson, FRS, was a British physicist and electrical engineer. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society and previously served as President of the Institute of Electrical Engineers (now the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) twice, in 1890 and 1896. He was awarded a patent in 1882 for his invention of the three-wire (three-phase) system for the distribution of electrical power. This system was used to distribute electricity. In addition, he worked in a variety of research fields related to electrostatics and electromagnetic. In the year 1890, he was assigned to the position of professor of electrical engineering at King’s College London, where he also served as the director of the Siemens Laboratory.

It is in his honour that Hopkinson’s law, which is the magnetic equivalent of Ohm’s law, was named.

Life and Career

In Manchester, John Hopkinson was born as the oldest of five children. He was the firstborn. He was a mechanical engineer, and his father was also known by the name John. Over the course of his education, he attended Queenwood School in Hampshire and Owens College in Manchester. After achieving the highest possible score on the rigorous Cambridge Mathematical Tripos examination, he was awarded a scholarship to attend Trinity College in Cambridge in the year 1867. He graduated from Trinity College in 1871 as a Senior Wrangler. At the same time, he was preparing for and successfully completing the exams for a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of London. Although Hopkinson had the opportunity to pursue a career in academia, he ultimately decided to pursue a career in engineering on his own. One of the Cambridge Apostles, he was.

After beginning his career in the engineering works owned by his father, Hopkinson moved on to become an engineering manager in the lighthouse engineering department of Chance Brothers and Company in Smethwick in the year 1872. It was in honour of Hopkinson’s application of Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetic to issues of electrostatic capacity and residual charge that he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in the year 1877. In the year 1878, he relocated to London to pursue a career as a consulting engineer. More specifically, he concentrated on refining his ideas regarding how to enhance the design and efficiency of dynamos. The three-wire distribution system that Hopkinson developed and patented in 1882 was the most significant contribution that he made. In 1883, Hopkinson demonstrated through mathematical analysis that it was possible to connect two alternating current dynamos in parallel. This was a subject that had plagued electrical engineers for a considerable amount of time: Additionally, he engaged in research on magnetic permeability at high temperatures, which led to the discovery of what would later be referred to as the Hopkinson peak effect.

In 1881, Hopkinson was awarded a British patent for the series-parallel method of controlling electric motors. This technology would go on to become a major step forward in the development of electric railways. In 1892, he applied for a patent in the United States, which resulted in an interference process being initiated against Rudolph M. Hunter, an American inventor who had been given a patent in the United States for the method in 1888.Although the United States Patent and Trademark Office upheld Hopkinson’s claim to priority of invention, the fact that his British patent had already expired before the conclusion of the case rendered him ineligible for a patent in the United States (his US patent, had it been issued, would have expired concurrently with his British patent).:

The position of President of the Institution of Electrical Engineers was held by Hopkinson on two separate occasions. During the second term of his presidency, Hopkinson put forth the idea that the Institution had to make the technical expertise of electrical engineers accessible for the sake of defending the nation. The Volunteer Corps of Electrical Engineers was established in the year 1897, and Hopkinson was promoted to the position of major in command of the corps.

![]()

Comments