In 2006, Mark Englis was set to become the first double amputee to conquer Mount Everest but tragic events later overshadowed his achievement. People were outraged that climbers chose to reach the summit for their own selfish gains over helping to rescue the life of David sharp.

Mark conquered Mount Everest for the first time as a double amputee on May 16, 2006. Mark finished his climb using two prosthetic legs made of carbon fiber that were tailored specifically for climbing. Early in the climb, he snapped one of them, but with the assistance of his climbing companions, he was able to fix it and continue the journey.

On May 15, 2006, Englishman David Sharp, 34, died from hypothermia in Green Boots Cave on Mount Everest’s Northeast Ridge. His passing sparked a debate that is still ongoing: what responsibility does a climber have when they come across another climber who is in dire straits?

It is commonly known that Mr. Sharp was passed by more than 40 climbers as they made their way up or down the mountain. One of them was Mark Inglis, who was the first person with two amputees to reach the top of Mount Everest. There was widespread public censure of the climbers’ behavior once it was learned that several of them had passed Mr. Sharp while he was dying in Green Boots Cave.

Even Sir Edmund Hillary, who is renowned globally for being the first to climb Mount Everest, voiced astonishment and fury. Additionally, Mr. Sharp’s Everest excursion firm, Asian Trekking, came under attack. The incident received a lot of media coverage and was the focus of a lot of newspaper pieces, magazine articles, documentaries, and novels.

Personally, I think a lot of the criticism was unnecessarily harsh and unfair, notably the condemnation of Mark Inglis and Asian Trekking.

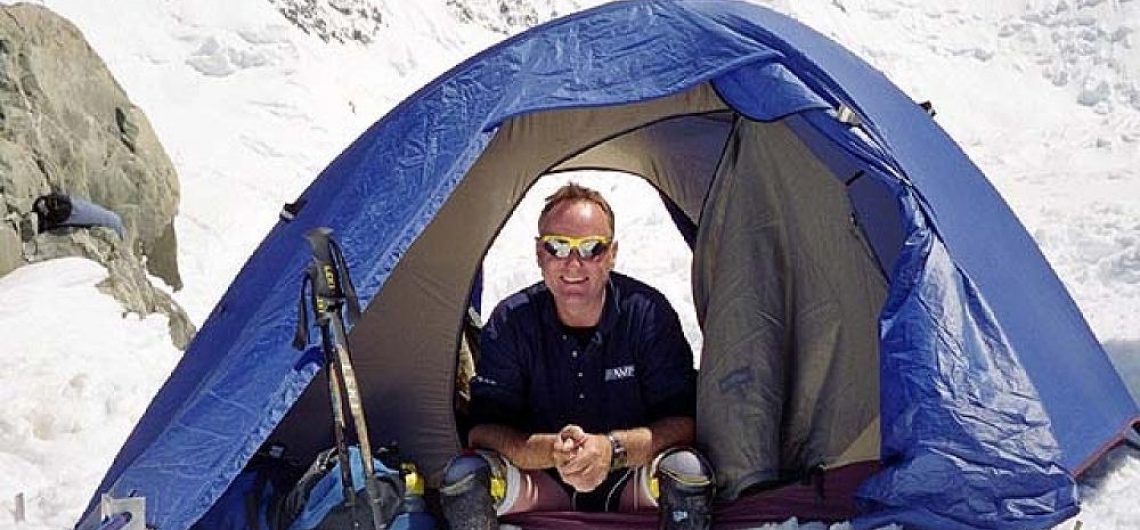

MARK INGLIS

On May 15, Mr. Sharp was utterly immobilized and close to passing out when climbers came upon him in Green Boots Cave. He had severe frostbite on his face, arms, and legs. Even with help, he was unable to stand up straight, and it took three guys to even drag him out of the cave and into the sunlight. It is generally known that no matter how many resources are applied, a climber who is immobilized in the so-called “Death Zone” over 26,000 feet cannot be retrieved. On Mount Everest’s Northeast Ridge in 2004, three Korean climbers perished. The absence of measures to save their lives was met with a similar uproar. A 14-person crew of experienced Korean climbers came back the next year to carry the bodies down the mountain. Only one body, still attached to the fixed line at 28,700 feet, could be found.

They worked for hours, but they could only transport the body 500 feet. They descended without having achieved their objective after burying the body with stones and holding a brief ceremony. When I was on the mountain in 2010, an English climber who had just descended from the North Side summit of Everest lost his vision, most likely due to cerebral edema. He soon passed out. He was left to freeze to death on the mountain despite the valiant efforts of a team of Sherpas who had been sent up to assist bring him down.

In Green Boots Cave, David Sharp’s situation was just as bad, if not worse.

What any climber ascending the Northeast Ridge that night could have done to assist Mr. Sharp, who was essentially locked in place at 28,000 feet, is difficult to fathom. On May 15, around 1 am, Mr. Sharp was found for the first time in Green Boots Cave. Even if a rescue effort had been initiated, it would not have been possible until daylight, which would have been several hours later. His situation would have been considerably more bleak at that moment.

Mark Inglis, a double amputee who took the brunt of the criticism, was also experiencing serious frostbite damage as a result of the extreme weather.

His condition was so bad that a Sherpa had to carry him down a section of the mountain. Additionally, he wasn’t an experienced excursion leader, guide, or Sherpa; he was a customer on an expedition team. He could simply not help Mr. Sharp because of his position.

If Mr. Sharp had been moving while he was in Green Boots Cave, I think other climbers, guides, and Sherpas who were aware of his danger were obligated morally and ethically to help. The majority of them would have picked up the phone. Dan Mazur was leading three clients up the Northeast Ridge just ten days after Mr. Sharp passed away.

At the base of the top, Lincoln Hall was sitting by himself in the snow. He spent the night on the ridgeline after his Sherpas had left him for dead the day before. Mr. Hall’s jacket was open and his expedition gloves were taken off when Dan came upon him. Despite being on the verge of death, he managed to stand and walk with help. Dan and his clients abandoned their summit bid and requested assistance. Mr. Hall was helped to safely down the mountain by a team of Sherpas who were dispatched up. Despite suffering severe frostbite damage, he lived.

Every climber is aware of the danger involved and accepts it, just like Mr. Sharp did on May 15.

Mr. Sharp would probably be the first to call this up. He made the decision to ascend alone, without enough oxygen, a radio, a satellite phone, or Sherpa assistance. He had made three attempts to ascend Mount Everest from the north face. He had suffered frostbite on his toes in earlier efforts and vowed bravely that he was willing to lose more in order to reach the top.

Mount Everest Basecamp vs Kilimanjaro

ASIAN TREKKING

The criticism directed towards Asian Trekking, the excursion planner Mr. Sharp selected, is as upsetting. Only a small percentage of individuals are aware of the distinction between a “guided” and a “unguided” climb. In a completely guided climb, professional guides accompany climbers the whole time they are on the mountain, and the group always moves as a unit.

In an unguided climb, the climbers essentially travel up and down the mountain on their own. Therefore, experienced climbers who like the independence and freedom that comes with going alone or with simply a Sherpa to help carry their gear should choose for unguided climbs.

On the North Face of Mount Everest, Asian Trekking provides two different unguided climb options: full service to the summit and no service above Advance Base Camp. In order to provide this “service,” Asian Trekking must secure the necessary authorizations, transport the climbers and their equipment to the Chinese Base Camp, then set up and staff the camps along the way to the summit.

If the climber chooses the no-service option, Asian Trekking’s obligation is fulfilled after they reach ABC. The climber is in charge of getting up and down the mountain above ABC with himself and his supplies. The no-service option is obviously only appropriate for extremely skilled, autonomous, and powerful climbers. And it costs a lot less money.

David Sharp enrolled in Asian Trekking’s no-service plan. There is no denying that he was a very skilled and experienced climber. With just two oxygen canisters and no Sherpa’s help, he decided to proceed alone. Additionally, it looks like he made the decision to climb to the peak quite late in the day, which is extremely risky even in ideal weather.

He was traveling without a radio or satellite phone, thus Asian Trekking was unable to monitor his whereabouts on the mountain. There is no proof, as far as I am aware, that Asian Trekking was made aware of the man’s terrible situation at Green Boot’s Cave until it was too late to organize a rescue operation. I don’t see the basis for criticism of Asian Trekking unless one holds the opinion that no-service, unguided climbs on Mount Everest ought to be prohibited.

I’ve been to the North Face of Everest three times and have encountered a lot of solo climbers. They have a lot of close friendships.

They were a tough, courageous, and self-reliant group, and each one recognized and accepted the risk of traveling by themselves with essentially no backup or radio communication. None of these climbers requested, anticipated, or desired that Asian Trekking or anybody else monitor their whereabouts. I am certain that a rescue attempt would have been launched right away, and we all would have contributed if any of them had gotten into difficulties and Asian Trekking had been informed.

This is not a justification for Asian Trekking or an apology. They make errors just like any other expedition firm. For instance, in 2011, when I was on the North side, I was going well and had plenty of time to reach the summit, but I had to turn back and descend at the First Step on the Northeast Ridge. The amount of oxygen we would require to reach the peak and return home safely was underestimated by my Sherpa. It would be simple for me to feel resentful of the Sherpa and Asian Trekking who hired him.

However, since I was climbing alone, it was ultimately my job to make sure we had adequate oxygen.

Except for Mr. Sharp himself, no one is to blame for what occurred to David Sharp, in my opinion. He would probably concur with this judgment, in my opinion.

Public Reaction to David Sharp’s Death

When this tragic event happened on Mount Everest, the public was not shy to express their outrage.

Sir Edmund Hillary

According to the news at the time, Sir Edmund Hillary was quite critical of the choice to not attempt to save Sharp, stating that it was unacceptable to let other climbers perish and that the drive to reach the summit had taken precedence over all other considerations. Also from him: “I find it scary how the mindset surrounding conquering Mount Everest has changed. The common goal of the populace is success. Lifting your hat, saying good morning, and walking by a man who was curled behind a rock suffering from altitude sickness was incorrect “. He expressed his horror at the heartless attitude of today’s climbers to the New Zealand Herald.

That they “don’t give a damn for anyone else who may be in distress and it doesn’t impress me at all that they leave someone lying under a rock to die” and that “I think that their priority was to get to the top and the welfare of one of the… of a member of another expedition was very secondary” are among their many other blatant disregards. Hillary referred to Mark Inglis as insane as well.

David Sharp’s Mother

David’s mother, Linda Sharp, doesn’t point the finger at other climbers. “Your obligation is to rescue yourself — not to attempt to save everyone else,” she told The Sunday Times.

David Watson

It’s unfortunate that no one who cared about David realized he was in difficulty, since “the outcome would have been much different,” said mountaineer David Watson, who climbed on Everest that season on the North side.

Sharp had collaborated with other climbers to rescue a troubled Mexican climber in 2004, according to Watson, who believed it was feasible to save Sharp. The morning of May 16, Phurba Tashi informed Watson.

Sharp’s identification was verified by Tashi when Watson went to his tent and gave him his passport. A Korean crew reported over the radio that Sharp, the climber wearing red boots, had died about this time. It is unknown if he summitted because his camera was lost but he still had his bag with him.

Related stories

- Green Boots the famous body on Mount Everest

- Francys Arsentiev, the sleeping beauty of Mount Everest

- David Sharp and the controversial death on Mount Everest

- Are there any reported deaths on Mount Kilimanjaro?

- Mark Inglis, the double amputee

- 7 Indians host tricolor on Kilimanjaro

- Fraudster climbed Kilimanjaro while on disability benefits

- Is Mount Kilimanjaro in Kenya or Tanzania?

![]()

Comments